Chinese state-owned COSCO shipping owns a 60% stake in Port of Chancay, and developed the port.

On the Peruvian coast, north of Lima, a monumental construction project rises out of the Pacific. The new deep-water port at Chancay, backed by China’s state-owned shipping giant, COSCO, is marketed as a triumph of international investment, a sleek new gateway linking South America to global markets. Politicians call it transformative. Economists and much of the media hail it as a keystone of development. The project’s glossy renderings present it as inevitable, modern, even enlightened.

But reading about Chancay, as I did this morning in this recent Inside Climate News article about the port, I felt like I was reading an obituary of the natural world. I visualized Chancay as a doorway through which the last (relatively) intact parts of the Earth will be fed into the machinery of global trade.

To call Chancay a “port” is to oversimplify this megaproject; it is the latest disaster in a global industrial system that converts forests, rivers, mountains, and wildlife into materials and commodities. And because of where it sits and what it enables, Chancay threatens to accelerate the unraveling of one of the planet’s last wild places: the Amazon rainforest.

Hundreds of miles to the east of Chancay, in a rainforest so lush and filled with species that scientists haven’t yet catalogued them all, new worries are percolating. Chinese investment is increasingly prominent, with Chinese machinery, trucks and workers seemingly everywhere. — A Massive, Chinese-Backed Port in Peru Could Push the Amazon Rainforest Over the Edge, Inside Climate News

This is not just another infrastructure project. It is an emblem of a growth and development ideology that sees every landscape as unexploited potential; a symbol of how rapidly we are erasing what little remains of a living world older and wiser than we are.

A Port that reaches far beyond the sea

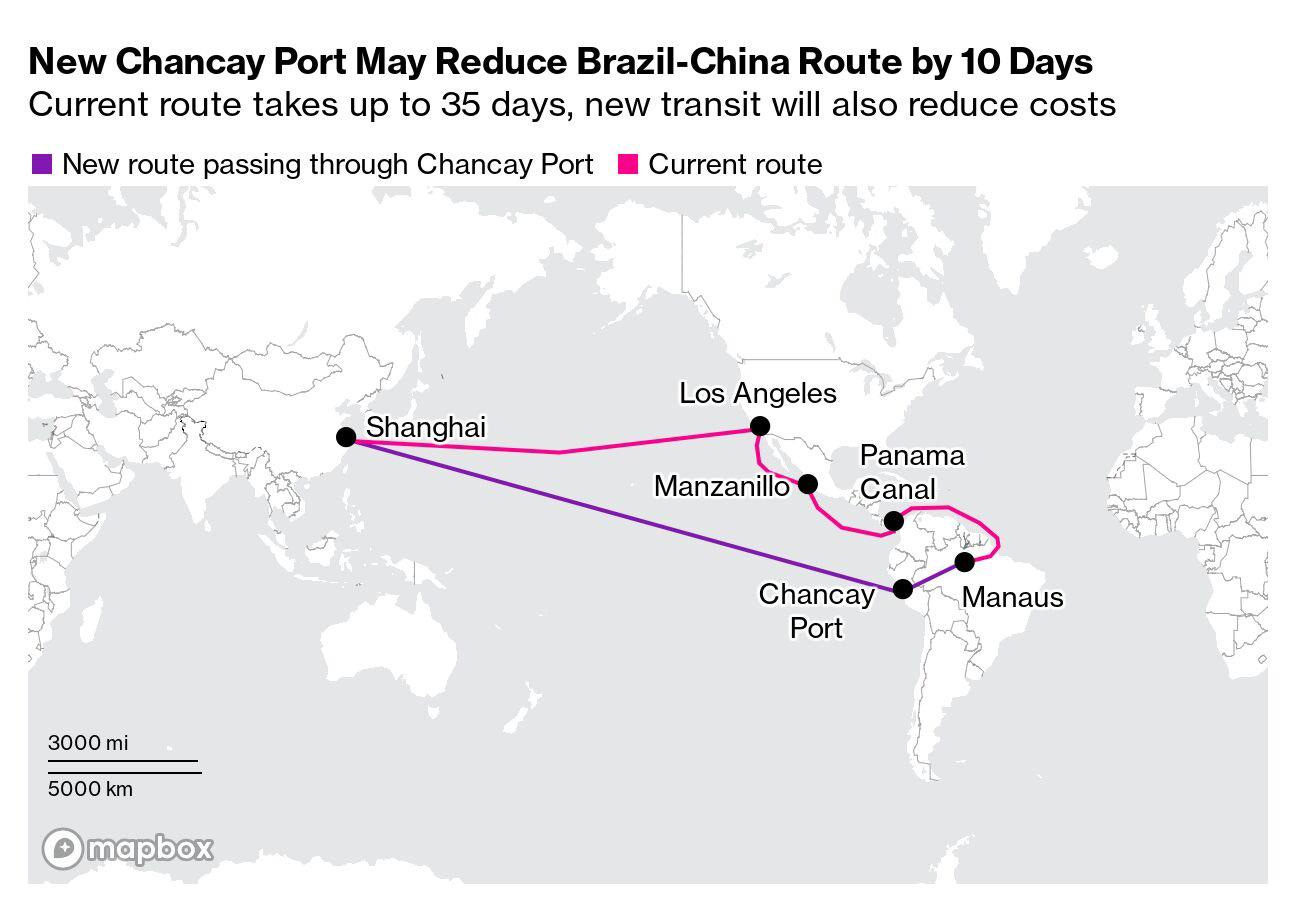

Map showing how the Port is reducing travel time for imports and exports to and from South America

Chancay is engineered to handle the largest container ships in existence; the same vessels that bind the global economy together in a ceaseless flow of goods and raw materials. What makes the port so consequential is not just its physical scale, but its reduction of time, distance, and cost between the Amazon basin and Asian markets. A shipping route that once required delays in the Panama Canal or detours around the tip of South America can now operate directly.

By making extraction more profitable, a port becomes a magnet for additional infrastructure: rail lines, highways, river corridors, industrial parks, factories, storage depots. Chancay’s gravitational pull extends far inland, across the Andes and into the forested heart of the continent.

When the Chinese shipping conglomerate COSCO signed the deal to buy a 60 percent stake in the Chancay port, most people guessed what would come next. “They need the roads,” Urrunaga said. “We knew that from the beginning—that this would come with a road.” What no one yet knows for sure is where exactly the new roads—or railways or waterways—might be. The port will likely beget many. — A Massive, Chinese-Backed Port in Peru Could Push the Amazon Rainforest Over the Edge, Inside Climate News

Already, old proposals for Amazonian road networks, trans-Andean rail links, and expanded river transport are resurfacing. Projects once dismissed as too destructive are being revived in the glow of Chancay’s promised prosperity. The port is not the end of a supply chain: it is the beginning of one.

China’s investments in the region are refreshing old plans in Brazil. Since the late 1960s, during Brazil’s military dictatorship (1964-85), the federal government has pushed for infrastructure in the Amazon Rainforest. Now, with the prospect of delivering commodities through the Pacific, Brazil is planning new routes cutting through the Amazon and reaching the other side of the Andes. — Brazil plans new Amazon routes linking the Pacific & China’s New Silk Road, MongaBay

This is how modern extraction works: a system of logistic connectivity reaches into forests and bays, fractures their integrity, and accelerates their destruction. A deep-water port is an invitation to reorganize entire regions around extraction.

We’ve seen this play out again and again with massive port projects. The Maasvlakte 2 in the Netherlands is a former shallower sea/coastal zone and was transformed into hardened industrial land, with quays, container yards, rail/road links, warehouses, and logistic infrastructure. Same with Port Botany in Australia. Same with Dhamra Port in India. Same with Roberts Bank, just across the border from me, in Canada.

Land and coastal ecosystems are always sacrificed, with cascading ecological impacts that lead to habitat destruction, water pollution, migratory species disruption, contamination, and biodiversity loss. New ports and port expansion is not a neutral infrastructure upgrade; it is a mechanism of extraction, commodification, and ecological erasure. A new or expanded port does more than facilitate trade; it reshapes the coast, obliterates ecosystems, and rewires land, labor, and environmental relations toward global commodity flows.

The Sheer Scale of Industrial Expansion

Ultra-Large Container Vessel (ULCV)

The Port of Chancay isn’t a modest regional dock. It is a modern industrial colossus built for the world’s largest container ships. Its initial phase opened with a berth front stretching 1,500 meters, four berths, and a deep-water draft (17.8 m) that lets Ultra-Large Container Vessels (ULCVs), ships carrying up to 18,000 standard containers (TEUs), pull right up to the dock. In practical terms: each of those vessels is roughly as long as four American football fields laid end to end and wide enough to cover several traffic lanes. The terminal is built to handle at least 1 million TEUs plus 6 million tons of bulk/general cargo and up to 160,000 vehicles annually in its first phase, with plans to scale up toward 1.5 million TEUs, a throughput only a handful of global ports match. Some projections foresee future expansion capable of accommodating ships up to 24,000 TEUs, which would make Chancay one of the deepest and most capacious ports on the entire Pacific coast of the Americas.

To put that in terms we humans can relate to: imagine a stream of mammoth steel leviathans, each the size of a floating skyscraper, arriving one after another, unloading construction machinery, EVs, electronics, household appliances, furniture, toys, and textiles, and loading thousands of containers with contents that range from farm commodities harvested deep in the Amazon to minerals dug from remote mountains, all funneled into global supply chains. Chancay reinforces a model where raw materials (minerals, timber, agricultural commodities) flow out, while manufactured goods flow in, anchoring our dependency and lock-in to commodity extraction and consumption cycles.

In addition to Chancay, China’s global logistics surge now stretches across South America, into the Port of Santos, Brazil’s largest port. In 2022 COFCO International, China’s state-owned agribusiness giant, won a 25-year concession to build a massive new export terminal, named STS11, at Santos. By 2025–2026, once fully operational, the terminal is slated to handle up to 14.5 million tonnes per year of soybeans, corn, sugar and other bulk commodities, a sharp leap from the roughly 4.5 million tonnes previously managed by COFCO at Santos.

Chancay isn’t an isolated port project; it is part of a broader strategy, with China controlling or operating at least 35–40 ports and terminals in Latin America. The development of the Chancay and Santos megaports underscores that what’s happening in Peru and Brazil is mirrored throughout South America and indeed the world: vast tracts of agricultural land, rainforests, savannahs, wetlands, and biodiversity-rich zones are annihilated and converted to grain, commodity, and export-volume.

The Amazon is not a resource, it is a living world

In policy papers, the Amazon is often reduced to functional metrics: the forest becomes an asset, a set of ecosystem services, a climate regulator, and a carbon sink to those who wish to exploit ecosystems in other ways. Framing ecosystems like the Amazon as carbon sinks or economic assets translates complex, living ecosystems into measurable economic or policy metrics that can be bought, sold, funded, or leveraged within global markets and regulatory systems. The big “green” organizations like The Nature Conservancy are especially guilty of this.

These abstractions and market manipulations hide the essential truth: that the Amazon is not a service provider. This immense, ancient forest is a living world unto itself, intricate beyond human comprehension.

Companies like to claim they “offset” destruction here by preservation elsewhere. But that’s not how nature works: we can’t destroy one ecosystem and point to another on a map and say “that will replace it.” No. There is nowhere destruction can be offset or “replaced” by preservation somewhere else. Every remaining wild community is already sustaining their own internal webs of life. The idea that one ecosystem can compensate for the destruction of another is a fantasy born of accounting, not biology.

I’ve never been to the Amazon, much less to South America. But like most people, I’ve read about it, watched videos about it, heard stories from people who’ve visited, and imagined it (usually my imaginings come with bugs crawling absolutely everywhere!). I do know that, like other biodiverse ecosystems, every acre of the Amazon is a labyrinth of relationships: trees communicating chemically underground; insects and fungi forming interdependent partnerships; birds and mammals dispersing seeds; predators shaping the behavior of prey; Indigenous communities living within and alongside it with knowledge accumulated over thousands of years.

What this Chancay port threatens to accelerate is not just the loss of a “carbon sink.” It threatens the disassembly of an entire world; a world that supports millions of species, many unknown to science, and ways of life that have existed since the earliest human migrations.

The dominant worldview makes the destruction of ecosystems legible as “development.” In the lexicon of global economics, an intact forest generates no revenue. A mined landscape does. A clearcut can be measured. A community displaced can be compensated. A species gone extinct has no price tag. A “carbon sink” can be traded. So long as value is measured in money alone, destruction appears as profit, and survival appears as inefficiency.

Under that logic, the Amazon Rainforest—a complex, beautiful, unique living being who can create rain, who feeds rivers, who shelters an incredible diversity of wildlife—is reduced to simply a reservoir of “unrealized economic potential.” And a port like Chancay becomes another tool for realizing it.

The global machinery of growth

To me, what Chancay represents most clearly is the irreconcilable existence of industrial expansion and natural communities. China can build megaprojects on astonishing timelines (as I like to say, they build megaprojects on their lunch break). What China’s Belt and Road projects have shown me more than anything else is that China can muster both will and manpower almost anywhere they want, particularly in places that desire foreign investment for development and growth. Multinational investment floods into a region overnight; construction crews reshape a coastline in months; and ships the size of skyscrapers pull into port the day it opens.

The Chancay port is not especially harmful because it is Chinese. It is harmful because it belongs to a global pattern that spans nations and ideologies; a Machine that treats economic growth as the supreme good, and the living world as the raw material needed to feed it.

Every country that participates in this paradigm—and all do—is complicit in the erasure of the planet’s last intact ecosystems. China builds ports and railways and roads and EVs. Western markets demand timber, minerals, cars, and agricultural products. Local political elites pursue development deals. International financial institutions underwrite them. Global consumers buy the resulting goods.

The global Machine that devours nature moves with mechanical efficiency; the natural communities who sustain life move according to their own timeline. Forests exist for millennia supporting life who need millennia of ancient continuity to live; the rivers fed by forests cannot be rerouted without consequences. Species driven to extinction do not return, and cultures uprooted by development cannot be replanted like crops.

Like the Terminator, the Machine does not stop. Ever.

No more “frontiers” left to lose

There was a time when wild places felt infinite to us ignorant humans, when there were forests beyond the map’s edge, oceans too deep and mysterious to exploit, mountain tops too high to mine, and Arctic lands too frozen and remote to industrialize. That is a world I have never known, and yet my heart aches for it.

That world is gone. We’ve expanded everywhere, and now we are exploiting everywhere and everyone. Some might say, as we have always done since the first human adventurer set out on a new path. The natural world today is not vast and untouched; it is small, fragmented, stressed, and pushed to its limits.

The Arctic, though still immense, is already fissured by oil extraction, mining, military installations, and shipping lanes opened by a warming climate. The ocean is being surveyed by mining companies and trawled to death by industrial fishing companies. The Congo Basin faces serious pressure from mining, logging, and agriculture. South East Asian forests in Indonesia and the Philippines are being strip mined for the metals to make car batteries and steel. The Amazon’s rivers are being dammed for electricity, the forest burned for cattle, soy, and roads, and the stripped and broken land mined to death. Even “protected areas” are pocked with roads, pipelines, and concessions. The Amazon still exists, still inspires, still supports life, but what remains is only the remnant of a world that was once whole.

If the Amazon is destroyed, that’s it. Once it is gone, it’s gone.

The illusion of “development”

Supporters of the Chancay port insist it will bring jobs, growth, investment, and opportunity to Peru. They frame it as a step toward modernity, a chance to “join the world economy,” a way to uplift communities that have long been marginalized.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and former President of Peru, Dina Boluarte

Xi said that Chancay, a 15-berth, deep-water port, was the successful start of a “21st century maritime Silk Road” and part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, its modern revival of the ancient Silk Road trading route. — Starting Latin America trip, Xi Jinping opens huge port in Peru funded by China, Reuters

These narratives are powerful. They are also incomplete.

Short-term economic gains always mask long-term ecological and cultural losses. The benefits of megaprojects rarely accrue to those whose lands are disrupted and never do anything but destroy wildlife and ecosystems. The benefits flow only upward to investors, corporations, and political elites. Fishermen in Chancay have already been displaced by construction that has damaged marine ecosystems and filled wetlands. Blasting and dredging have cracked nearby houses. And the forests that will eventually feed the port’s traffic lie far from the communities promised prosperity.

The coastline has already changed because they covered a bay with rubble, now the beaches are sanded. There are no fishing sites, and the sea has receded many meters, which also caused the fishing pier to lose depth. Many vessels got stranded. We are witnessing tremendous destruction, and the project has just started. — Local Chancay resident, Contesting the Anticipated Infrastructural City: A Grounded Analysis of Silk Road Urbanization in the Multipurpose Port Terminal in Chancay, Peru, Annals of the American Association of Geographers, Nov 2024

This pattern is familiar because it is repeated across the globe: corporations extract profits and the ecological costs remain local and permanent.

The fundamental problem is that development framed as economic throughput is indistinguishable from liquidation. When mountains are “ore deposits,” forests are “timber,” rivers are “power,” and communities are “labor pools,” we’ve lost the plot. Living communities are dissolved into supply chains and in the end, what have we got to show for it? Stuff, stuff, and more stuff, overflowing and ultimately useless to life on planet Earth.

But, destruction inflates GDP, therefore governments have every incentive to continue it.

What Chancay tells us about ourselves

The Chancay megaport is a monument to human supremacy; to the belief that we can infinitely expand, engineer our way out of limits, and impose our ambitions on the natural world without consequence. It embodies the idea that humanity is exempt from ecology, that growth is destiny, and that wildness is a resource waiting to be consumed.

But the planet we live on does not share those beliefs. This planet, our only home, obeys the laws of physics, ecology, and biology. Species die when their habitats disappear. Rivers collapse when their watersheds are stripped. Forests burn when they are fragmented and dried. Cultures unravel when the land that sustains them is taken.

We mistake our power for safety. We are wrong. Chancay and all industrial projects are accelerating the fraying of the web of life, a web all living beings utterly depend on for our existence. Industrial development is making us more unsafe every millisecond it continues.

The Reckoning Ahead

I imagine businessmen in expensive suits flying across the Amazon in private jets, looking out the window and thinking, “I can conquer that.”

The idea of “endless frontiers” was always a myth—one rooted in conquest, of landscapes, of other beings’ homelands, and of other peoples—and even that myth is collapsing under the weight of reality. The world that once seemed so large is now frighteningly small, and the wild places that once seemed invulnerable are down to their last defenses.

Chancay is not the first step toward the destruction of the Amazon, nor will it be the last. It is yet another in a long line of megaprojects destined to ruin countless lives, yet another moment when humanity is pressing forward into a future built on a fantasy, even as the natural world is saying “I have no more to give.”

Progress, as we have defined it, has consumed forests, rivers, coastlines, and species beyond counting. It has brought us to the edge of a world no longer resilient enough to absorb the impacts, and yet we continue, because stopping feels unimaginable to most.

A tragedy is a grave, consequential downfall that feels both avoidable and inevitable: avoidable because the warning signs were there, and inevitable because something in human nature—pride, denial, greed, blindness, momentum—makes us unable to change course. In ecological terms, tragedy is knowing what’s happening, knowing what it means, knowing what will be lost, and continuing anyway.

The tragedy is not just that ecosystems are dying. The tragedy is that we continue to kill them knowing exactly what their loss means, and knowing there are no others waiting beyond the horizon or on some other planet, despite the psychotic ambitions of the tech-bros. The last wild places of Earth are not resources. They are the remaining fabric of a living planet.

Once that fabric is torn, no amount of engineering, investment, or economic growth can stitch it back together.

There is no substitute for what we are losing. There is only loss, and the unbearable question of how much more we will take before there is nothing left to save.

A mine in the Amazon Rainforest.

Recent Comments