Anthropocentrism did not begin with the West. It is far older, far more widespread, and far more deeply rooted in the human species than any single empire or cultural tradition. What Western colonization did was industrialize this mindset. To locate the origins of anthropocentrism within one civilization is to misunderstand both the long arc of human history and the nature of colonial ambition itself.

I. Anthropocentrism is older than any empire

Anthropocentrism, the presumption that humans occupy the center of meaning, value, and authority on Earth, is an ancient orientation. Long before the first kings, priests, or merchants inscribed their deeds in clay or papyrus, humans were altering ecosystems simply by moving through them. The great dispersal of our species out of Africa, beginning roughly 60,000–70,000 years ago, reshaped continents. Wherever humans arrived, waves of extinctions followed: giant marsupials in Australia, mammoths and mastodons across the Americas, enormous birds in New Zealand and Madagascar. These losses were not caused by Western civilization, or any civilization at all, but by small bands of foragers equipped with nothing more than stone tools, spears, and fire.

The earliest agricultural societies intensified this pattern. Civilizations in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, the Yellow River basin, the Sahel, and the highlands of Mesoamerica cleared forests, diverted waterways, exterminated predators, and reorganized entire landscapes around irrigation and grain. They viewed land not as a living community but as a system to be optimized for human survival and hierarchy. By the time the first empires emerged, humans had already spent thousands of years remaking the world in our own image. Anthropocentrism, in other words, is not a Western invention. It is a deep human tendency that predates writing, farming, and empire.

This does not mean all societies were equally destructive or equally divorced from ecological reality. Some indigenous cultures developed rich traditions of reciprocity, restraint, and ecological knowledge that moderated the human appetite for domination. However, the underlying belief that humans have a special entitlement to shape the world is detectable across continents and millennia. It is a species-wide impulse, not the cultural property of the West.

II. Colonization has always been anthropocentric

If anthropocentrism is ancient, colonization is one of its political expressions. We often speak as if “colonization” refers only to the European empires of the 15th–20th centuries, but the behavior itself—the movement of peoples into new lands, the claiming of territory, the subordination of nature and others—is universal. Human history is a long relay of expansions: groups displacing groups, kingdoms annexing neighbors, empires rising and subsiding like tides. Every major civilization has participated in some form of conquest or colonization. To pretend otherwise is to romanticize the past or selectively edit it.

The Mongol Empire rolled across Eurasia in the 13th century, absorbing peoples and extracting tribute over a domain larger than any European empire before the age of sail. The Han dynasty expanded deep into southern China and Central Asia, displacing or assimilating numerous cultures along the way. The Bantu migrations spread across sub-Saharan Africa, displacing earlier hunter-gatherer populations. Polynesian navigators settled island after island across the Pacific, often overwhelming endemic species, and leading to the extinction of over a thousand bird species. In the Americas, the Aztec and Inca realms extended imperial control over diverse groups through warfare, tribute, and political coercion.

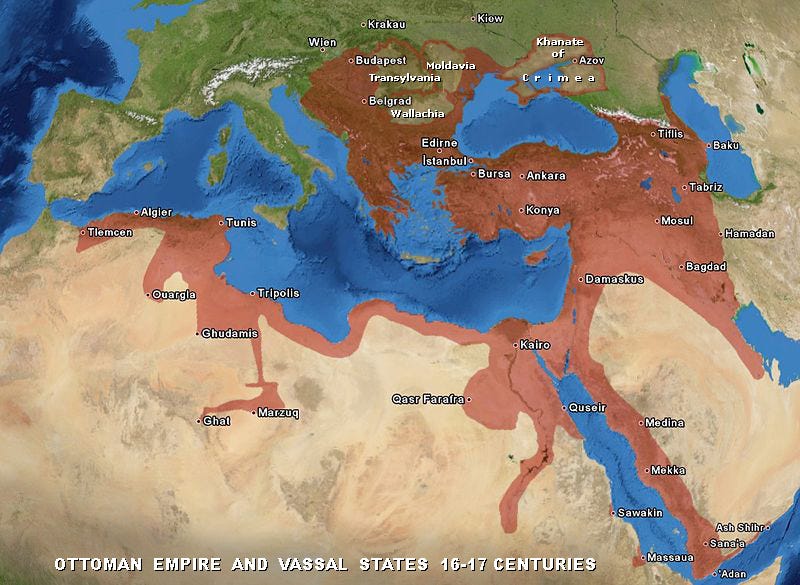

The Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries

The Ottoman Empire provides an especially clear example. Spanning from the late 13th century until its formal end in 1922, it ruled parts of southeastern Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa for over 600 years. It conquered lands, absorbed peoples, imposed taxes, regulated trade routes, and extracted resources on a scale rivaling or exceeding many Western powers. Enslaved people from Europe, the Caucasus, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa were bought, sold, and transported across imperial borders. Many male slaves were forcibly castrated and the survival rate for the procedure was notoriously low. Women and girls were trafficked into domestic service, agricultural labor, and the imperial harem, where life could range from relative privilege to extreme coercion, confinement, and sexual servitude.

Children were also subject to state-sanctioned seizure. Through the devşirme system, Christian boys from the Balkans were taken from their families, converted to Islam, and trained as Janissaries or court administrators. While some rose to high power, the practice was nonetheless a forced extraction of human beings as imperial “resources.” Women’s legal status across the empire varied by class and region, but many lived under patriarchal systems of guardianship, limited property rights, arranged marriages, and vulnerability to trafficking. These practices were not anomalies; they were integral to how the empire structured human life to serve the ambitions of the state.

The Ottoman Empire also reshaped and damaged the natural world in ways characteristic of large, extractive states. Forests across the Balkans, Anatolia, and the Levant were cleared for shipbuilding, charcoal production, and military expansion, accelerating erosion and reducing wildlife habitat. Wetlands were drained for agriculture, marsh cultures disrupted, and waterways diverted or heavily taxed, often undermining traditional ecological uses. The empire’s destruction of nature illustrates the anthropocentric pattern seen across empires: vast territories understood primarily as resource reservoirs to be harvested, taxed, and reorganized to support an expanding state.

Seen in this light, the Ottoman Empire demonstrates that the logic of colonization—claiming land, “resources” (i.e., nature), labor, and bodies as instruments of power—was not unique to the West. It was a pervasive human pattern expressed in different forms across civilizations.

Many of the hierarchical structures that characterized the Ottoman Empire have modern echoes in parts of the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia as legacies of patriarchal, authoritarian, and resource-extraction systems that long predate and outlast any single empire. In some Gulf states, for example, the kafala labor system binds millions of migrant workers, mostly from Africa and South Asia, to employers in conditions that human-rights groups describe as “contractual slavery,” including passport confiscation, coercion, and forced labor. In countries such as Mauritania, forms of hereditary servitude and caste-like structures persist despite formal abolition. And more than a few states, strict male-guardianship laws, curtailed property rights, and limited political participation sharply constrain the autonomy of women and girls. While these conditions vary widely across the Muslim world, their existence underscores a larger point: the impulse to treat certain classes of humans as subordinate resources is not confined to any one culture, religion, or era. It is a recurring human phenomenon wherever power goes unchecked.

A stark contemporary example came to global attention during preparations for the FIFA World Cup in Qatar. Journalists, human-rights researchers, and visitors reported that tens of thousands of migrant laborers from Nepal, India, Bangladesh, Kenya, and the Philippines worked under conditions widely described as “modern slavery.” Bound by the kafala sponsorship system, workers often had their passports confiscated, were unable to change jobs or leave the country, and lived in overcrowded labor camps while working in dangerous heat. Numerous investigations documented unpaid wages, forced labor, and preventable deaths during stadium and infrastructure construction. While the Qatari government denies the term “slavery,” many observers, including those who visited during the construction boom, described what they saw as workers effectively owned by their employers. This example shows that systems of domination over human bodies, including labor extracted through coercion, lack of mobility, and fear, are not relics of past empires but active features of the modern world.

The same mindset that treats human workers as subordinate resources is often mirrored in the way natural systems are managed. In Qatar, the rush to build stadiums, roads, and hotels for the World Cup led not only to extreme exploitation of migrant labor but also to massive environmental disruption. Qatar leveled desert ecosystems to create artificial turf fields, dredged coastal areas for new ports, and extracted groundwater to support construction and landscaping. Construction displaced native plants and wildlife, with little regard for long-term ecological consequences. The logic is the same as in the kafala system: landscapes and nonhuman beings exist primarily to serve human ambitions, just as workers’ lives and labor do. Both illustrate a broader anthropocentric principle: that anything standing in the way of rapid economic or political goals, whether human or natural, can be subordinated, extracted, or transformed to serve those in power.

A port in Qatar, dredged and filled for human use.

III. What Western colonization actually changed

Beginning in the late 15th century and accelerating over the next four centuries, European empires fused older patterns of conquest with something historically unprecedented: industrial power. Fossil fuels, mechanized extraction, scientific forestry, industrial mining, global plantations, and legal systems transformed what conquest meant. Western colonization turned anthropocentrism into an engine with planetary reach. It reorganized entire continents for extraction: beaver fur and timber in North America, rubber in Southeast Asia, sugar in the Caribbean, minerals across Africa and South America. It perpetuated a worldview in which land was “property,” forests were “resources,” and wildlife was “game” or obstacles to be relocated or eliminated.

Western imperialism endowed the impulse to dominate with industrial leverage. A worldview that had once been constrained by muscle, wood, and wind became amplified by coal, steel, and capital. The result was a transformation of Earth’s atmosphere, oceans, soils, and living systems into the wreckage we see today. The West did not create anthropocentrism, but it did accelerate it.

In the decades since Western empires have receded, other states have taken up the mantle of industrial-powered expansion. China is the most prominent example, not because it is uniquely ambitious, but because it combines enormous population, industrial capacity, and a centralized political structure capable of mobilizing vast resources toward geopolitical aims. As with historical empires, the driving anthropocentric mantra of China’s industrial and economic ambitions is that nature is here for us to exploit. The Belt and Road Initiative has enabled Chinese companies and state-backed entities to build ports, mines, railways, dams, and energy infrastructure across Africa, South America, Central Asia, and the Pacific, often extracting minerals, timber, and fisheries at scales that echo or exceed earlier colonial enterprises. Countries burdened with unsustainable debt, eroded sovereignty, or environmental degradation are left to absorb the externalities.

China’s sweeping territorial claims in the South China Sea, its large-scale damming of transboundary rivers, and its rapid expansion into rare-earth mining show that industrialized anthropocentrism is not tied to Western identity but to modern power itself. Any state with enough industrial momentum—regardless of culture, ideology, or civilizational narrative—can reproduce the same pattern: the belief that vast landscapes, ecosystems, and distant peoples exist to be reorganized for national advantage.

IV. The real lesson

To claim that anthropocentrism originated with Western colonization is to miss the larger story. It absolves humanity of its long entanglement with domination while misdiagnosing the root of our current ecological crisis. Our impulse to place humans at the center of everything is ancient; the technologies that allow that impulse to overwhelm the planet are recent. If we want to understand our predicament, we must recognize these truths.

Western imperialism did not invent anthropocentrism; the seed was always there, inside us, long before the caravels and cannons set sail.

To confront the ecological and moral challenges of our time, we must see ourselves clearly. We are not the victims of one culture’s worldview; we are a species whose oldest habits have collided with its newest powers. Our task now is to imagine a different orientation, one that does not place humans above the living world, but within it. And to do that, we must first tell a truer story about how we got here.

Recent Comments